The Changing Landscape in Obesity Treatment

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently released a draft of their new guidance for the development of anti-obesity medication (AOM) for weight reduction. Feedback will be accepted until April 8. This guidance, replacing that published in 2007, attempts to incorporate both changes to the AOM landscape and advances in our understanding of obesity as a condition. We believe that this guidance will have implications for trial design and efficacy benchmarks and for the competitive landscape of AOM.

In addition, although this guidance provides important clarity on a variety of points, we believe that several outstanding questions remain unanswered. Here are our thoughts on several key topics from the draft guidance.

Trial design

Inclusion criteria and endpoints

Both the FDA guidance and a recent commission from The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, which was published several weeks after the guidance and developed by 58 experts, highlight body composition as a key component of obesity. The Lancet Commission characterizes obesity as a condition of excess adiposity, and the guidance notes that AOM-induced weight loss in patients with obesity should occur primarily from fat content reduction. A component of this guideline is the FDA recommendation to measure body composition with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) or an approved alterative in a representative subset of subjects (Note:

Waist circumference measurement is not an approved alternative).

It is interesting that the FDA guidance differs from The Lancet Commission with regard to use of body mass index (BMI). The Lancet Commission recommends against using BMI as the sole criterion for obesity, noting that it is an imperfect predictor of fat content. The FDA guidance acknowledges limitations to the use of BMI as a proxy for body fat but does not view alternative measurements of adiposity as superior to BMI; this is due to either limitations in accessibility or challenges with reproducibility. The FDA guidance accordingly supports the standard inclusion criterion of BMI ≥30 kg/m2 in AOM trials. The difference between the two groups’ stances may reflect their different goals: an update to the theoretical framework of obesity by The Lancet Commission, and an update to real-world practices by the FDA.

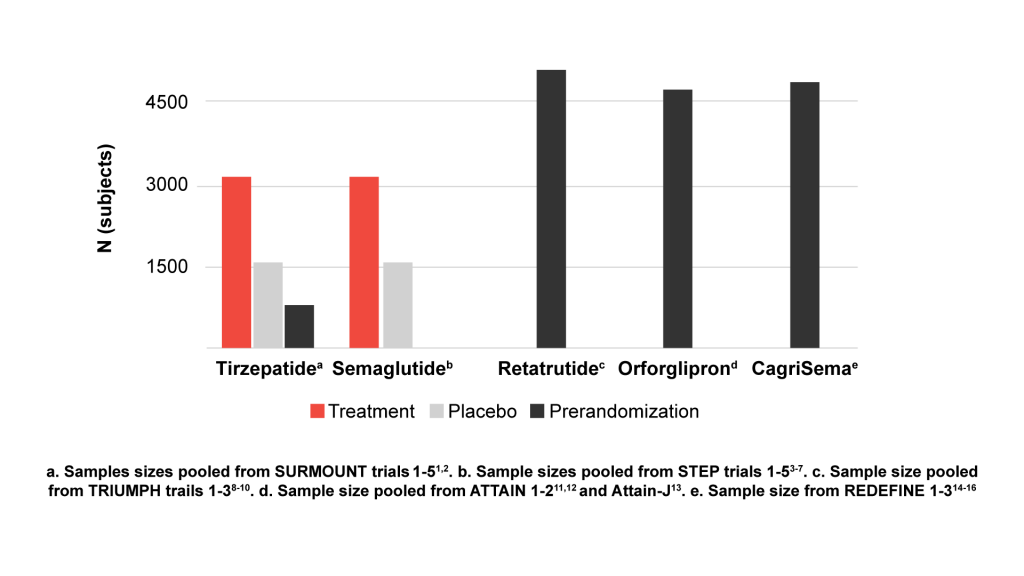

Sample size for safety data

The FDA guidance recommends a sample size of 4500 participants to assess safety: 3000 for the investigational drug, and 1500 for placebo. It is important to note that safety analysis can be based on data from multiple trials. Recent phase 3 trials of tirzepatide1-2 and semaglutide3-7 have each achieved this sample size when pooling subjects from their various phase 3 trials, and ongoing trials for newer AOMs, such as retatrutide8-10 and orforglipron11-13 (Eli Lilly and Company) and CagriSema14-16 (Novo Nordisk) are enrolling >4500 participants. We are curious as to whether enrollment was scaled to ensure 3000 participants in the investigational drug arms.

Patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D)

Phase 3 trials for tirzepatide and semaglutide were enriched for patients with T2D using drugs for glycemic control, and there are reports of these drugs being prescribed for patients with prediabetes (particularly during the delay between approvals for diabetes and obesity) and for patients who meet neither disease’s criteria but could still benefit from treatment. The FDA guidance builds on this approach by stating an expectation that trials be enriched for patients with T2D who are using drugs for glycemic control, a requirement that will affect up-and-coming AOMs in the developmental pipeline. It is interesting that the guidance also advises that an indication for the delay of T2D onset will need to be supported by establishing the clinical benefit(s) of the delay; delayed biochemical diagnosis of T2D alone would most likely not suffice. Thus, although future AOM trials will need to be enriched for patients with T2D, approval of these drugs for T2D treatment will be more challenging.

In addition, it is expected that once-weekly basal insulins for T2D treatment—molecules with pharmacokinetic profiles that are fundamentally different from those of the daily versions—will enter the US market in the coming years. Study sponsors will need to determine whether they will differentiate between once-weekly and once-daily users in their analysis of T2D subgroups.

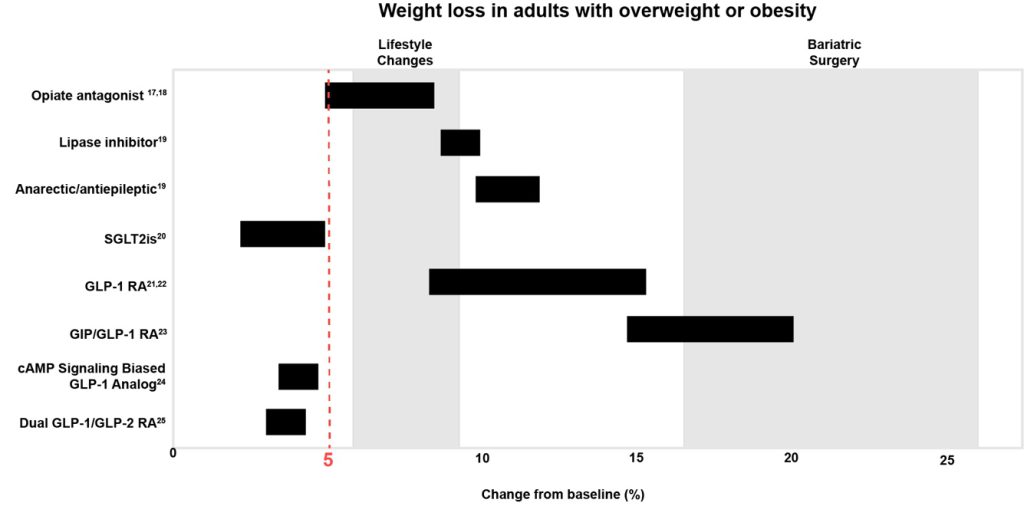

Efficacy

Historically, a mean percentage weight reduction that is at least 5% greater than that in the control arm has been considered the threshold for clinical efficacy, and the FDA guidance now specifies that this benchmark must be met for a drug to be considered effective for weight reduction and maintenance in patients with obesity. It is common for drugs developed for other conditions (eg, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors [SGLT-2is], selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]) to cause weight reduction that is statistically significant yet shy of this mark, so this guidance ensures that drugs marketed as AOMs produce clinically meaningful weight reduction.

cAMP = cyclic adenosine monophosphate; GIP = glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide;

GLP-1 = glucagon-like peptide-1; RA = receptor agonist.

The FDA guidance also specifies that the 5% weight reduction must be maintained for at least 1 year, which addresses an important concern among healthcare professionals and patients about the long-term efficacy of newer AOMs. It also appears to establish a need to both define the maintenance dose itself and delineate key time points around goal attainment and maintenance.

Competitive landscape

The FDA guidance also states that results will not be applied to drug classes as a whole and that each drug will need its own trial, a distinction that could influence the ability to obtain certain approvals. For example, insulins are a major class of weight-inducing drug, and the ownership of most insulin forms by Lilly and Novo Nordisk gives them the edge of trialing their individual insulins with their weight loss drugs. In addition, Lilly owns several psychotropic and anticonvulsant drugs whose classes are associated with weight gain, which potentially confers an advantage with approval of tirzepatide for treatment of the weight gain induced by these same medications.

Conclusions

The AOM landscape continues to evolve rapidly. This FDA guidance helps address these changes by codifying certain clinical trial practices and taking steps to ensure the real-world efficacy of future AOMs. It will be interesting to see how the major pharmaceutical players respond to the guidance and to compare the draft with its final version.

References

- Le Roux CW, Zhang S, Aronne LJ, et al. Tirzepatide for the treatment of obesity: rationale and design of the SURMOUNT clinical development program. Obesity (Silver

Spring). 2022;31(1):96-110.

- Eli Lilly and Company. A study of tirzepatide (LY3298176) in participants with obesity or overweight with weight related comorbidities (SURMOUNT-5). ClinicalTrials.gov

identifier: NCT05822830. Updated December 11, 2024. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05822830

- Novo Nordisk A/S. STEP 1: Research study investigating how well semaglutide works in people suffering from overweight or obesity (STEP 1). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier:

NCT03548935. Updated November 19, 2021. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03548935

- Novo Nordisk A/S. Research study investigating how well semaglutide works in people with type 2 diabetes suffering from overweight or obesity (STEP 2). ClinicalTrials.gov

identifier: NCT03552757. Updated November 9, 2021. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03552757

- Novo Nordisk A/S. Research study to look at how well semaglutide is at lowering weight when taken together with an intensive lifestyle program (STEP 3). ClinicalTrials.gov

identifier: NCT03611582. Updated November 11, 2021. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03611582

- Novo Nordisk A/S. Research study investigating how well semaglutide works in people suffering from overweight or obesity (STEP 4). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier:

NCT03548987. Updated January 19, 2022. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03548987

- Novo Nordisk A/S. Two-year research study investigating how well semaglutide works in people suffering from overweight or obesity (STEP 5). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier:

NCT03693430. Updated July 6, 2023. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03693430

- Eli Lilly and Company. A study of retatrutide (LY3437943) in participants who have obesity or overweight (TRIUMPH-1). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05929066.

Updated February 27, 2025. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05929066

- Eli Lilly and Company. A study of retatrutide (LY3437943) in participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus who have obesity or overweight (TRIUMPH-2). ClinicalTrials.gov

identifier: NCT05929079. Updated February 28, 2025. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05929079

- Eli Lilly and Company. A study of retatrutide (LY3437943) in participants with obesity and cardiovascular disease (TRIUMPH-3). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05882045.

Updated January 24, 2025. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05882045

- Eli Lilly and Company. A study of orforglipron (LY3502970) in adult participants with obesity or overweight with weight-related comorbidities (ATTAIN-1). ClinicalTrials.gov

identifier: NCT05869903. Updated February 27, 2025. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05869903

- Eli Lilly and Company. A study of orforglipron in adult participants with obesity or overweight and type 2 diabetes (ATTAIN-2). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05872620.

Updated February 27, 2025. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05872620

- Eli Lilly and Company. A study of once-daily oral orforglipron (LY3502970) in Japanese adult participants with obesity disease (ATTAIN-J). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier:

NCT05931380. Updated February 28, 2025. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05931380

- Novo Nordisk A/S. A research study to see how well CagriSema helps people with excess body weight lose weight (REDEFINE 1). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier:

NCT05567796. Updated February 24, 2025. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05567796

- Novo Nordisk A/S. A research study to see how well CagriSema helps people with type 2 diabetes and excess body weight lose weight (REDEFINE 2). ClinicalTrials.gov

identifier: NCT05394519. Updated March 13, 2025. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05394519

- Novo Nordisk A/S. A research study to see how well CagriSema helps people in China with excess body weight lose weight (REDEFINE 6). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier:

NCT05996848. Updated March 7, 2025. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05996848

- Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc. A safety and efficacy study of naltrexone SR/bupropion SR and placebo in overweight and obese subjects participating in an intensive behavior

modification program. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00456521. Updated December

17, 2014. Accessed March 12, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00456521

- Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc. A safety and efficacy study of naltrexone SR/bupropion SR in overweight and obese subjects. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00567255. Updated

November 21, 2014. Accessed March 12, 2025.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00567255

- ADA Professional Practice Committee. 8. Obesity and weight management for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of care in diabetes–2025.

Diabetes Care. 2025;48(suppl 1):S167-S180.

- Zheng H, et al. Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors in non-diabetic adults with overweight or obesity: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol.

2021;12:706914. doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.706914 - Saxenda. Summary of product characteristics. European Medicines Agency; 2025.

- Wegovy. Summary of product characteristics. European Medicines Agency; 2025.

- Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021;387(3):205-216. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2206038

- Sciwind Biosciences announces positive topline results from phase 3 clinical trial of Ecnoglutide (XW003), a long-acting cAMP signaling biased GLP-1 analog, in adult

patients with type 2 diabetes in China. PR Newswire. January 2, 2024. Accessed

February 20, 2025. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/sciwind-biosciencesannounces-

positive-topline-results-from-phase-3-clinical-trial-of-ecnoglutide-xw003-along-

acting-camp-signaling-biased-glp-1-analog-in-adult-patients-with-type-2-diabetesin-

china-302023591.html

- Zealand Pharma. Dapiglutide. Zealand Pharma. Accessed February 20, 2025.

https://www.zealandpharma.com/pipeline/dapiglutide/

Share